Episode 4

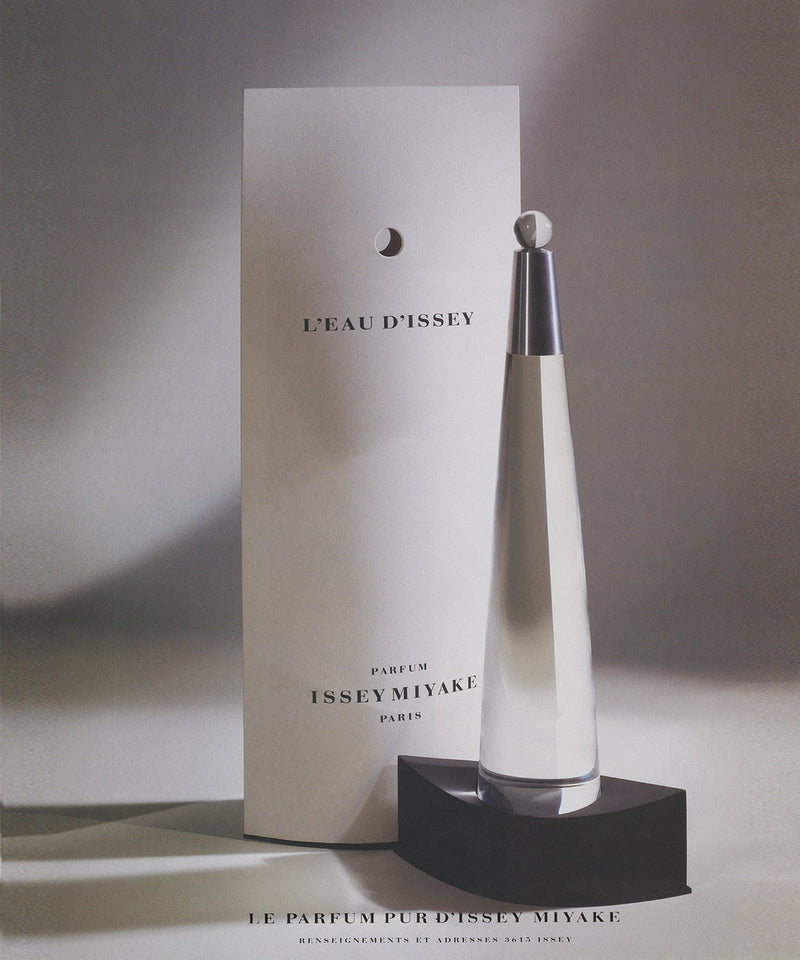

“Protein Revolution #2”

by Kazuhide Sekiyama (Spiber)

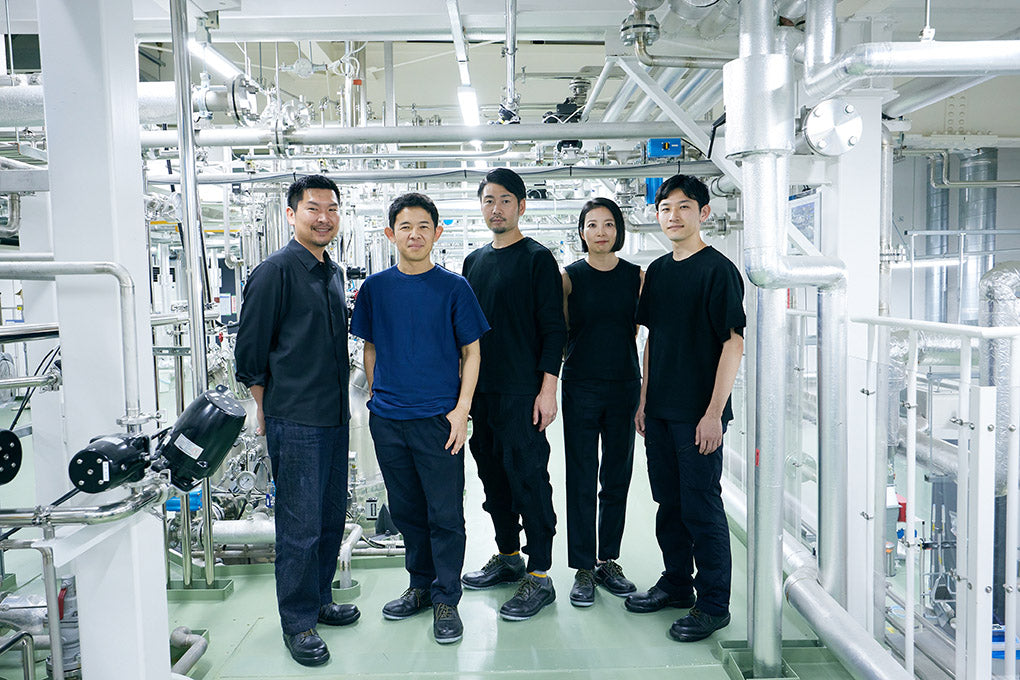

“Brewed Protein™” is a structured protein material developed by Spiber. In Episode 3, we talked about the technology behind the product, outlined how it functions as a material, and explored some of its potential. In Episode 4, our focus is on ideals versus realities in material development and what it means for the people who support its research, manufacturing and business, and for the Earth 100 years from now. The scope of the dialogue expands because this new material is very much a product of passion, belief and imagination of a better tomorrow. Our participants are Kazuhide Sekiyama from Spiber, Yoshiyuki Miyamae from A-POC ABLE ISSEY MIYAKE, and design engineers Manabu Nakatani, Nanae Takahashi and Takahiro Hoshino.

──Tell us again about the process by which you developed the Brewed Protein™ material. The original idea came from spider threads that you had been researching since you were a student. You went on and founded Spiber, creating technology for precision fermentation of proteins by microorganisms. What were the technical hurdles in doing this?

Kazuhide Sekiyama (“Sekiyama” below): As I look back on it, there was no single thing that was particularly arduous, no one barrier to be overcome. The normal technical hurdles were already daunting enough. When you overcome one, you often encounter another giant wall standing behind it. Intuitively, I would say that we had around 1,000 hurdles to overcome in the research and development of the Brewed Protein™ material. It was very much a process of plodding away through each of them.

Obviously, within that, there were cases where advances in technology brought significant gains in productivity, or a certain function suddenly improved. But there was no single break-through; it was the sum of all of our efforts until that point. There are very few dramatic episodes in which someone had a single great idea that achieved major technical results immediately.

──You had a wide scope of research-- genetic engineering, materials engineering, biotechnology. Are you saying that even if there was a significant advance in one area, it did not represent any real progress unless everything functioned well together?

Sekiyama: Yes, that's right. That was always how it felt. That is why we had to keep plodding along. There was a mixture of things that we could do and things we could not do but that we might be able to sometimes, and the more the research moved forward, the greater number of things we could do. In that process, we became aware of “things that we can probably do a bit better,” which led to the discovery of new and exciting possibilities. We still have a long road ahead of us, but our enthusiasm for development remains high.

Yoshiyuki Miyamae (“Miyamae”below): Sekiyama-san, when you started your research as a student, could you imagine it developing into something like this?

Sekiyama: Actually, I had a sense that “maybe I can pull it off.” But I also knew that it would be something stupendous if I did. I still have a lot of uncertainty, but compared to 20 years ago, I have far more confidence.

──I'd like to ask about the people and facilities that support this work. When you develop a material that has no predecessors, you essentially need to build everything from zero right? How did you do that?

Sekiyama: In the fundamental aspects, I've enjoyed the support of people who have very flexible and creative minds. You need to understand that our research and development mostly fails to go according to plan. When results are disappointing or a roadblock is encountered, you have to remain flexible and tell yourself “Maybe it would work if we did this instead” or “This might be of use in a different area of research.” You have to be the type of person who is able to think positively and continue moving forward, or you will quickly give up. So what happened is that we naturally developed an organization led by a core of flexible, creative people.

Miyamae: That kind of mentality is extremely important. Flexibility and optimism are crucial to starting anything new. You can see that in the manufacturing of A-POC ABLE ISSEY MIYAKE. Basically, we have no concept of failure and no time to be disappointed. Maybe we have a lot of dreamers in our team in that regard. (Laughs).

Sekiyama: You might be right. (Laughs). This may sound a bit extreme, but if you look at the history of the universe over millions and billions of years, it will ultimately make very little difference if humanity is destroyed or if the Earth is swallowed up by the sun. From that perspective, I sometimes feel like there is very little difference regardless of whether our business succeeds or fails. However, this technology of designing proteins from the genes, and manufacturing it using precision fermentation is, I believe, certainly achievable by someone, maybe not by an earthling. Obviously, I would be happier if we were the ones to do it.

── This is technology with an impact, even on such a vast scale. Certainly, what we mean by “comfortable living” has changed significantly over time and in different environments. When you try to take materials that are optimized to individual requirements for clothing, housing and hardware, and technology that allows you to design the structure of proteins and efficiently mass-produce them, there is almost infinite potential.

Sekiyama: Certainly, when you think about the concept of “what is comfortable and uncomfortable,” how the material feels on your skin and how it functions are very important points, but closer to the foundation is the idea that in times of confusion, for example war, upheaval, or famine, you are absolutely uncomfortable. I think this is a common perception for all people. And I think there are many people who understand that what we are trying to do is important in preventing these sorts of things from happening or at least reducing their risk. Those people tend to gravitate toward Spiber.

Miyamae: This is all quite magnificent, but I think it is something everyone can sympathize with as addressing a crucial problem for society. Maybe these are the kinds of perspectives and ways of thinking that we need in order to revolutionize and make advances in the future.

Sekiyama: Perhaps we are thinking on too grand a scale, but such conversations are relatively normal at our company. It is extremely important to have a reason why you are working. I personally am inspired by the excitement of “maybe I can do something great.” In that sense, curiosity tends to win over uncertainty and fear. Spiber certainly has a lot of people who dream big in the best possible way.

──Having some dreamers on your team may be why it is able to stay so creative. Do you immediately know whether a person will be the right fit for the team?

Sekiyama: When interviewing applicants, we always ask, “The company may not be around next year. Are you okay with that?” As a matter of fact, I've asked this question ever since the early days. It goes without saying that everybody is working their hardest to make sure that does not happen, but it is a challenging business and not something we are doing because we want stability. I think it is only fair to let people know from the start that “that's the kind of company Spiber is.” People who are able to accept that and want to join us are usually the type that are willing to step up when required.

──Out of curiosity, if stable growth is not the objective of the business, what sort of KPIs or other metrics do you use to evaluate it?

Sekiyama: Obviously, at the individual level, we verify how much has been achieved in terms of the topics being researched and developed, and how different units will have different targets. As a KPI for the entire company, I am only thinking about “how much impact we can have on humanity.” Naturally, that is something you cannot measure in the short term. It is often the case that something very useful at a certain point in time may become problematic a century later. Therefore, instead of thinking about “what is correct and what is incorrect,” we want to consider “what do I want to do right now, what brings me the most excitement.” Without that, I don't think you will be able to summon up much energy.

On that point, people who really think they “want to help humanity through this research” tend to gravitate to our company and tend to have the energy to quickly overcome any setbacks they may encounter.

── Do you think that energy extends outward from Spiber to investors and collaborators like A-POC ABLE?

Sekiyama: I think that's exactly right. For startups like us, it is vital that investors, development partners and others who support our development understand the value of our business. In that regard, we have been very blessed over the past 15 years. We have been through many business crises, but we have always enjoyed the support of these people and been able to overcome problems. I think a large part of this was because they could share at a very deep level the idea that “humanity will be better off with this material and technology.”

This is how we have grown and developed, so we have very little concept of “Spiber as a company.” Yes, we have positions within the organization, but we don't really think in terms of insiders and outsiders. Rather, anyone who shares the idea of “wanting to do something important for humanity” and who wants to work with us is part of the group. For the people who work at Spiber, if it is easier to achieve that goal by having a position with us, we want them to have that position, but if it is easier to achieve by working with us externally, then that is what we want them to do. That is our attitude.

Miyamae: So you are able to join the team by sharing a grand objective. Our manufacturing is not something that we can do entirely on our own within the company. It is important that we develop as many collaborators as possible. It's something that the A-POC ABLE Design Engineering Team can certainly understand.

Nanae Takahashi (“Takahashi” below): I agree. As I listen to Sekiyama-san, I can feel my perspectives broadening. I think I need to give greater consideration to what other challenges we can take on in the projects we are working on together.

Manabu Nakatani (“Nakatani” below): I want to dream even bigger! (Laughs). Not just me, but my team members, and the people at the factories we do business with.

Miyamae: That's true. Sekiyama-san has given us a lot of food for thought.

Nakatani: I have a question for you, Sekiyama-san. This company called “ISSEY MIYAKE” has always manufactured apparel and products and delivered them to customers. Behind this has always been an approach to manufacturing that involves constant innovations in processes and technologies. But we never reveal to outsiders what those processes and technologies are, no matter how wonderful. What are your thoughts on that? As I listen to you speak, I am impressed by the idea that if the technologies and manufacturing processes we have developed benefit humanity and the earth, we should make them public, and we need to share them with as many people as possible.

Sekiyama: I don't know if this is a satisfactory answer, but we are in exactly the same situation. Patents are an example. The purpose of the patent system is to publish and share excellent inventions to the world so that they lead to the next innovations. In return for publishing excellent, important ideas, you are given exclusive rights to the business for a certain period of time. On the other hand, there are many different enterprises with many different motivations, and if different components of technologies become dispersed, it becomes a barrier to the penetration of excellent solutions that could create a better future, and that is something we need to avoid. That is why we develop component technologies and file for patents in areas that we might need. This requires a lot of money, but doing so gives us a dominant position that makes it easier for us to attract the funding required for research and development and infrastructure investments, which in turn makes the technology and business expand rapidly.

The primary objective of our business is, as I said before, the public good. When you consider what is necessary to achieve that, it is not desirable for the required technologies and patents to be dispersed among many different owners. We have to be able to integrate them, or there will be major losses for humanity and the Earth. Therefore, the first step for us is to pioneer as much technology as possible. Then, when those technologies are established, we can make them available for use by the people who need them.

Nakatani: Interesting. The question is how to maximize the goal.

──I'd like to talk about Spiber's business. It is distinguished not just by this material called structured protein, but by the company's ability to manufacture processed goods like fibers and threads in-house using its technology. Why is that?

Sekiyama: It's because we had to. We understood that we had to be able to manufacture fibers and threads for Spiber to progress on to the next phase.

──In Europe, there was a startup called Renewcell that recycled cotton from old clothing into cellulose, but it went bankrupt. The company was widely praised for its ability to improve the sustainability of fashion, but it ultimately had problems building a supply chain that could manufacture thread and fabric from its materials. Is this relevant to your situation?

Sekiyama: Yes, I can understand the difficulties they encountered. Simply put, it is extraordinarily difficult for a startup to bring a completely new material to the public and have it accepted. It's a “chicken and egg” problem. For example, if you mass-produce on a large scale and try to land orders, you will need to confirm QCD (quality, cost, delivery). But confirming QCD means that you have to build your own factory, put it in operation and actually mass-produce. This requires an enormous amount of investment. But when you ask financial institutions and investors for the money, they are usually not inclined to say yes unless you have the orders confirmed in advance.

In other words, you need to test mass-production to win orders, and you need investment in order to test mass-production, but you need orders to get investment. So you are in this situation where there is nowhere to turn and your cash flow becomes difficult. This is not limited to fibers and threads; it happens to all startups in materials and manufacturing.

Miyamae: So that is the reason why startups that develop new technologies like textile recycling and sustainable materials do not end up implementing them?

Sekiyama: Yes, that's right. For example, Toray Industries began developing carbon fibers in the 1960s, but decades passed before they expanded into production. Toray already had a synthetic textile business and lots of funds, so it was able to keep investing in materials development and research, but startups do not have existing businesses capable of producing those funds and need to continue to attract investments. It might be more doable if you have a business model that looks to slowly expand production volume, increase buyers and grow the business, but for manufacturers of new materials like ourselves, you will go absolutely nowhere if you don't build a large factory and begin to mass-produce. Obviously, prior to mass-production, you need to invest in a pilot production line and research facilities.

Spiber was established 16 years ago, and if you count my research at the university, I have been doing this for around 20 years, which is something close to miraculous. Even without major sales, we have been able to raise the funds that we require, continue our research and development, and build a factory for mass-production. I think many startups in new materials have considerable struggles in that regard. It is very daunting to have to compete head-on with existing products that have costs and quality levels refined over the course of several decades.

Miyamae: I understand what you are saying. Why was Spiber able to make it all the way to mass-production while spending 20 years in development?

Sekiyama: It is not that we made it all the way, but that we are finally at the starting line. For Spiber to become a real materials manufacturer, we have to be cost competitive with existing materials, and that will require scaling up 10 or 100-fold. The factory in Thailand that began operation a couple of years ago is only now at a scale where it may just be viable as a business.

Spiber's value as a business is certainly something that will only come in the future, but it is a fact that we have been able to use data from Thailand to precisely estimate our long-term cost structures and LCA (Life Cycle Assessment).

As I said earlier, for the business to succeed, we need to have a complex array of component technologies spanning different areas and layers. Spiber has accumulated a predominant number of necessary patents compared to its rivals. In fact, we have almost no rivals left and have been lucky enough to attract investment so far.

──You already have a mass-production plant in operation and are gradually bringing your materials to apparel and other products, but you still only consider yourself to be at the starting line.

Sekiyama: That is correct. You can build a factory, but obviously, the capacity utilization rate will not be very high at the beginning. It's a process of trial and error. Only when you reach 100 or 1,000 times the scale of an experimental plant do you begin to see problems. While you're doing that, you also need to make steady, incremental improvements in efficiency and productivity. It is difficult to calculate costs, or rather, if you do it the regular way, you end up with an unbelievably high number. (Laughs).

Miyamae: I understand what you are saying. You want to change those mechanisms. We also need to build new frameworks for each of our manufacturing processes, and at the initial stage, ordinary cost calculations are not at realistic levels. However, new manufacturing is not about immediately turning a profit. Sometimes, there are things you need to do first to create value, and it is important that you patiently continue to move forward to turn ideas into realities.

For example, we are unable to make direct investments in Spiber, but we do want to use Brewed Protein™ in ways that will enable as many people as possible to experience its quality and comfort. That is why, at this moment, we want to start with the things that are possible for us. Part of that is communicating the development of the material, the manufacturing, the products, and the stories and passions behind them. All of them will help to maximize value and potential.

Sekiyama: It is really encouraging to hear that people view us like Miyamae-san. For example, in Japan alone, there is reportedly about 8 million tons of wood that have been thinned from forests but have gone unused. With that as the raw material for Brewed Protein™, we can mass-produce protein for livestock food. How much? We can replace a large percentage of the corn Japan currently imports. That indicates the potential for a livestock industry that is not dependent on imports, which contributes to economic security.

Global conflicts and other international upheavals have caused wheat prices to skyrocket. Obviously, in times like these, having the technologies and plants that enable us to supply all of our food domestically makes a huge difference. We have without a doubt been more successful than anyone else in technology that uses microorganisms to produce protein from agricultural residue. At the current point in time, we have filed for 591 patents, including PCT (Patent Cooperation Treaty) filings, and have acquired rights for 205 of them.

But that alone is not sufficient. Bringing that technology to society in the form of mass-production requires launching a new industry. Our first steps in that direction are the factories in Thailand and the United States. As I discussed earlier, there is a “chicken and egg” problem with investments that makes it difficult to accelerate this. We have discussed many ideas and proposals with public agencies and others, but obviously, nothing is simple. There are many technologies in Japan like Spiber with the potential for large social impacts. We ourselves need to think more creatively about support mechanisms and public support so that these businesses can be accelerated.

──On the question of assistance and support, does Spiber have any other unique approaches besides investors and collaborators like A-POC ABLE?

Sekiyama: Yes. We have advisors on technology and engineering. These are researchers and engineers who are experts in fermentation and fibers, and became legends in the development of Japan's world renowned fermentation and textile industries. They tend to be in their 70s and 80s, but are all healthy and active, and they are deeply insightful. There are about 30 of them in total, and when, for example, we want to build a production plant, they quickly gather around and, grumbling sometimes, work with us to figure things out. I'm only guessing, but I would expect that the generations with these sorts of technologies and insights have largely passed on in other countries.

──Is that because the transformation of the industrial structure in Japan was late in comparison with Europe and the United States?

Sekiyama: That's part of it, but it's also because Japan values and preserves manufacturing technology. For example, we value the insights and technologies of engineers who have been involved in the entire process from the research and development of synthetic textiles to implementation as an industry. They teach us a lot, often in a spirit of volunteerism. Some tell me, “We come around because it is fun.”

At Spiber, our team designing plants and devices is very young, all in their 20s and 30s. Most of them graduated from the local technical college (National Institute of Technology, Tsuruoka College). From the point of view of our legends, they are more like grandchildren, but the legends are very good about providing them with insights and teaching them about living technologies.

──Brewed Protein™ is the foundation for a completely new technology, which makes it important to have the insights of these legendary figures.

Sekiyama: Yes. Also, what has been good for us, is that these people come from many different companies. Rather than receiving technology assistance from a specific company, we can turn to veterans in, for example, the textile industry that hail from companies like Toray Industries, Asahi Kasei, Teijin and Kuraray. Sometimes this means that legends from this company have completely different experiences and perspectives from the legends of another company, but we work with that, and are able to arrive at our own final decisions. We've been able to be selective in a good way, and to develop the technology without becoming biased in any one direction.

Miyamae: We encounter similar situations in the manufacturing of apparel and textiles. There are lots of technologies that you need to learn about now or you will lose. I often wonder what would happen to those technologies if this or that particular person were to quit.

Nakatani: We need to cooperate with the factories to build new processes for clothing manufacturing. This is not something we can do on our own.

Takahashi: That applies to traditional dyeing and weaving craftsmen. There are many things that can only be accomplished with the technologies that they have. Lots of A-POC ABLE products depend on the technologies of specific individuals.

──Both Spiber and A-POC ABLE are firms at the forefront able to completely change society and manufacturing processes, and behind this ability are technologies and insights that have been quietly and steadily passed down. It will be no easy thing for textiles, apparel and fashion to change the world, but there are some items that do so, like jeans. They started out as work clothes for coal miners, but became a cultural and generational symbol like in the counterculture. When you think about that, perhaps clothing made with Spiber's fibers will symbolize a turning point, a kind of a revolution, maybe several decades from now, maybe just a few years from now. Or maybe structured protein will solve our shortages of food, farmland and materials. What do we need to do to make that happen?

Sekiyama: As one example, choosing textiles like those developed by Spiber will build a foundation for human society 100 years in the future. There may be only a handful of people who believe that now, but it actually will happen. There is no doubt in my mind that we can do this. The amount of change is very small if you think of it in terms of a single piece of clothing for a single person, but the cumulative effect is what will build a new industry. As this gradually grows, we may be able to support the social foundations of the next age. At the risk of repeating myself, we have in that sense only just made it to the starting line. The goal is a world in which society is supported by proteins made with precision fermentation of microorganisms.

We need to communicate all of this. It is difficult to imagine the entire scale just by looking at items in a store that contain Brewed Protein™ fibers. That is why I'm very happy to be able to talk like this with people from A-POC ABLE, and I hope we can continue to work together to get the message out. I hope that in 100 years, Brewed Protein™ fibers will be instrumental in supporting society of the future.

Miyamae: To this point, the world of fashion has often focused on constantly changing trends, and it has been difficult to communicate deep messages. Today, however, the situation has changed. Fashion needs to work closely with the rest of the world to evolve. Clothing manufacturing requires that we confront essential, foundational questions, and this becomes a driving force for us at A-POC ABLE as we try to change the world through manufacturing processes. Our objective must be to create apparel of unprecedented excellence, but for this to happen, it will be crucial that we carefully and thoroughly communicate the potentials and values this will open up. That is one of our purposes for these DIALOGUES. There are many challenges to tackle, but we need to work from broader, longer-term perspectives and not just focus on short-term results.

You talked about jeans a moment ago, and in the late 1960s, jeans were a symbol of the antiwar movement. Denim jeans became a symbol of peace and freedom for young people. What this indicates is that at major transition points, people and societies use objects and style to express their perceptions and thoughts. The world currently confronts any number of intractable problems like armed conflict, poverty and climate change. It will be difficult to solve them without changing our traditional mechanisms and structures. I think that it is exactly in times like these that Spiber and Brewed Protein™ materials are needed.

KAZUHIDE SEKIYAMA

Director and Representative Executive Officer / Founder at Spiber Inc.

Born in Tokyo in 1983. Entered the Faculty of Environment and Information Studies, Keio University in April 2001. Assigned to the laboratory of Masaru Tomita, the director of the university’s Institute for Advanced Biosciences, in September of that year. Moved to Tsuruoka in 2002 to research the artificial synthesis of spider silk. Established Spiber Inc. together with student colleagues in September 2007 while still in the doctoral course. Currently promoting the industrialization of “Brewed Protein™,” an artificially structured protein material that will be instrumental in the achievement of sustainable well-being and a recycling-based society.